Are You Getting the Volatility You Paid For?

November 18, 2025

The intrinsic orientation of capitalism is towards the future — the present is assessed principally through the lens of how the world is expected to evolve. Yet the future is (in complex, non-linear systems) ontologically uncertain — indeterminate — the outcomes do not yet exist and they depend on the decisions, interactions, and interpretations of the market. There is no way to predict an uncertain, unknowable, and open future and so any expectations or predictions about the future are always imagined and fictional.

So how do markets coordinate activities and predict futures that cannot be predicted? They do so by converging (in a distributed way) around symbolic abstractions — narratives and other signs that condense complexity into more simple, transmissible concepts (i.e. money, securities, prices are all symbolic abstractions themselves).

These abstractions are often layered and recursive (especially narratives), each layer abstracting away reality to a greater extent, much like how the symbol “Internet” abstracts away the OSI stack, underlying material components and infrastructure, and physical energy that connects the world.

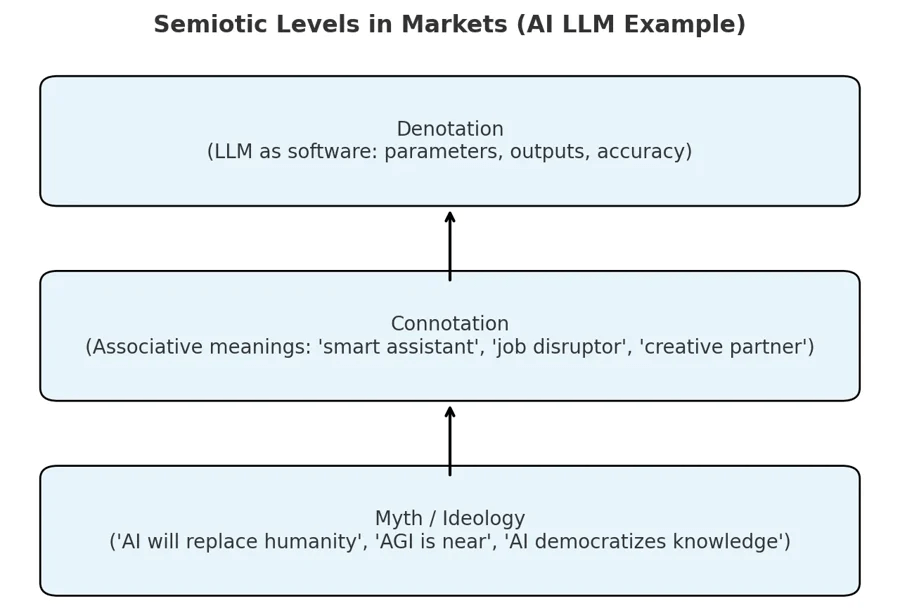

This is the idea of higher-order signification (see Barthes work in semiotics), where symbols no longer refer to direct objects or material realities but are re-signified into other layers of meaning, in multiple layers of signification. This is immediately apparent by looking at the total market cap of the stock market relative to the GDP (above). The market cap to GDP ratio encodes the extent to which investor expectations about the future have floated above the real productive base. The current AI wave is a great example of high-order signification in practice:

While the third-order connotation can unfold into reality (AI will certainly have a tremendous impact on the economy), it likely obfuscates various frictions and overly coherent activities which can get lost in abstraction. For instance, adoption of LLMs can slow down as enterprises figure out best practices, workflow integrations, evaluation and alignment, security and data access, and data integration.

So what does this mean for the active discussions around consensus investing?

Possibly a few things: